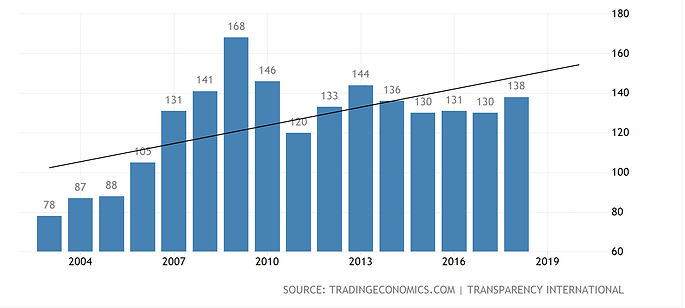

Transparency International ranked Iran 138 out of 180 countries in the 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index, scoring 28 out of 100; which has progressively deteriorated over time. Under the Islamic Republic the three main types of corruption that, regardless of whether they are governmental or non-governmental, undergo in Iran are of nepotism, embezzlement, and bribery. This section shows the research that has been done on these types of corruption in Iran.

But before addressing corruption in more recent Iranian political affairs, it is worth mentioning that the most notable form of informal governance during pre-revolutionary Iran was dawrah which literally translates to 'circle', and is the act of a group of people who organise regular meetings in specific locations such as hidden rooms, but the most popular rendezvous being coffee houses. The discussions that occurred in these meetings included the topics of politics, religion and so on; with aims of keeping the spirits of their beliefs alive and practicing freedom of expression. Some of the actions that they'd take include informally and illegally publishing and spreading written papers on an ideal state, writing against the one they were living under. This act of informal governance was most prominent after the 1953 Coup d'etat, when democratic prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh was overthrown in favour of the monarchy (Bill, 1973). A unique characteristic of the dawrah system is how they are personalistic; information is spread through individuals of different dawrah groups, thus 'certain personalities become key transmitters' and this 'invests them with a disproportionate share of power and influence in society' (Bill, 1973).

These practices lasted until the 1970s, when the same Shah of Iran was exiled and a Islamic Republic came into play in 1979. There is little evidence of whether these dawrah forms of informal governance are still carried out under this current regime.

Nepotism -Fesad-e siyasy داسف یسایس )

Nepotism is interestingly a normalised form of corruption in Iran, whereby promoting family members as close associates or simply pertaining status in high ranking positions is seen as a good deed under the Islamic Republic.

A notable example of nepotism in Iran is with the President Hassan Rouhani and his brother Faridoon Rouhani, who is his appointed special advisor.

Besides the fact that nepotism occurs in that his brother is his special advisor, in 2017 Faridoon Rouhani was arrested on allegations of financial irregularities. He was taken to a hospital from prison, and was released within twenty-four hours. There is suspicion of further corruptive practice here, as many prisoners with severe medical conditions aren’t granted these privileges, whether they’re political prisoners or not (Celal, 2017).

Nepotism is a major and recurring issue in Iranian politics, another notable example being from the former president Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), who appointed his brother Ali Khatami as his chief of staff during is presidency, and not to mention the Larijani brothers, who are known for holding high status in the political system: Ali Larijani, the speaker in parliament; Sadeq Larijani, the head of the judiciary until 2019; and Mohammad-Javad Larijani, secretary of High Council for Human Rights in the subdivision of the judiciary.

The fact is, there are plenty of examples that demonstrate how family ties, are always valuable in gaining status in Iran; in all spheres of life. But this has gained normalcy in Iran, as the Islamic Republic has justified nepotism in the name of helping someone who is close to you, who you owe the help to. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei ‘read a verse from the Quran about Prophet Musa’s plea to God to appoint his brother Haroon as his deputy’ (Ibid). This shows how the embedment of Islam and politics has given concepts a whole new meaning and perhaps made certain acts that foreign countries would deem unfair, as acceptable in the name of Islam.

Embezzlement-Fesad-e eghtesday ve maly داسف یدتصتقا و یلام

Since the Islamic Republic was established after the revolution in 1979, the people of Iran relied on the new constitution and government to rid the country of oppression and corruption that the monarchy was accused and guilty for, as was outlined continuosly by Ayatollah Khomeini, namely in his book Velayat-e Faqih (Islamic Government). But it didn't take long after the new regime settled, for evidence to show that cases such as embezzlement, haven't changed since the monarchy was abolished, if not gotten worse.

One of Iran’s most well known corruption court cases since the country became an Islamic Republic was a case of embezzlement in 2019, when the Iranian courts tried thirteen ‘petrochemical industry executives charged with embezzling 6.6 billion euros ($7.4 billion)’ as they had established ‘shell companies overseas to circumvent sanctions imposed’ during the Ahmadinejad presidency (Motevalli, 2019).

Another case of embezzlement comes from Labour Minister Mohammad Shariatmadari’s son-in-law Mohammad Hadi Razavi who was charged with embezzlement ‘after receiving around $51m in loans from banks which he has failed to pay back’ (Radio Farda, 2019). Tehran’s deputy prosecutor accused Hadi Razavi of bribing bank managers of ‘Sarmayeh Bank’ in order to receive a fraction of this sum; which was used for travelling purposes, ‘buying luxury cars and real estate’ (Ibid).

For reasons such as the harsh sanctions imposed on the country since 2012, Iran definitely doesn’t show a shortage in embezzlement cases. But this doesn't take away from it being the consequences of the restrictive regime itself, that has undoubtedly created an environment that fosters corruptive acts and has its own fair share of corrupt activity within its own political sphere. For instance, especially after the war between Iran and Iraq (1980-88), Mahdavi explicitly creates a case that the Mullahs 'introduced new ways of embezzling money and wealth of the people in Iran' as this act is 'embedded in the culture of this system', which is (Mahdavi, 2019).

Bribery-Fesad-e akhlaghy داسف یقلاخا

It can be difficult to point out how bribery actually begins in a country and how it is spread, eventually becoming a popular act for those who are in a position of power and advantage.

The ‘Business Anti-Corruption Portal’ on the well-known software company’s website GAN, displays a useful profile on corrupt activity in Iran. The profile, with information from the Global Competitiveness Report (2015-16), shows the many forms of bribery that occur in Iran, for instance: ‘executives report that bribes and irregular payments are often exchanged in return for obtaining favourable court decisions.’ This interestingly links back to the form of nepotism in the Judiciary mentioned earlier with the Larijani brothers. The Guardian in fact published an article in 2016 alleging that the head of the judiciary ‘Ayatollah Sadeq Larijani, possessed 63 personal bank accounts filled with public funds’ (Dehghan, 2016). Since Sadeq Larijani is no longer head of the judiciary since the beginning of 2019, his successor Ebrahim Raisi has reported numerous cases of bribery under the judiciary.

This demonstrates that the government is not only harbouring nepotistic traditions, but these individuals also commit further crimes of bribery within their status and structure; thus abusing their power.

Bribery in Iran also occurs on a more everyday and local level amongst consumers and students. A study done by Mohammad Atashak regarding corruption in teaching in Tehran, for instance, concluded that the corruption in the education system lies within 'field of recruitment, appointment and promotion, teacher renumeration, teacher presence at school, [and] teachers-pupils/ parents relationships' (Atashak, 2011, p462).

Thus, to summarise, the spread of bribery in society owes to how individuals choose to imitate those above them, which in turn has the impact of 'universalising the inefficiencies and injustices of the activity' (Johnson, 1985, p448).

Bibliography

Atashak, M. (2011) 'Identifying Corruption among Teachers of Iran', Procedia: Social and Behavioural Studies Vol 29 pp. 460-463.

Bill, J.A. (1973) 'The Plasticity of Informal Politics: The Case of Iran', The Middle East Journal Vol. 27 (2) pp.131-151.

Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4325054

Accessed on 11th December 2019

Celal, S. (2017) ‘Nepotism in Iran’s political system’ by Anadolu Agency

Available at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis-news/nepotism-in-iran-s-political-system/868383

Accessed on 24th November 2019

Dehghan, S.K. (2016) ‘Iranian judicial authorities attempt arrest of MP’ in The Guardian

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2016/nov/28/iranian-judicial-authorities-attempt-arrest-of-mp-mahmoud-sadeghi

Accessed on 24th November 2019

Johnson, H.L. (1985) 'Bribery in International Markets: Diagnosis, Clarification and Remedy', Journal of Business Ethics Vol. 4 (6) pp. 447-455.

Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25071534

Accessed on 13th December 2019

Mahdavi, D. (2019) '40 Years of Embezzlement in Iran, the Largest Cases' by Iran Freedom

Available at: https://iranfreedom.org/en/2019/11/08/40-years-of-embezzlement-in-iran-the-largest-cases/

Accessed on 13th December 2019

Motevalli, G. (2019)

Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-09/iran-court-tries-13-in-7-billion-petrochemical-fraud-case-mehr

Accessed on 24th November 2019

Radio Farda (2019) ‘Minister’s Son-In-Law in Iran Accused of Embezzling $50 million’

Available at: https://en.radiofarda.com/a/minister-s-son-in-law-in-iran-accused-of-embezzling-50-million/29954692.html

Accessed on 24th November 2019

Transparency International (2018)

Available at: https://www.transparency.org/country/IRN

Accessed on 24th November 2019

Wood, T.L. (2019) ‘Time is running out for Iran’s corrupt mullahs’, The Washington Times

Available at: https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2019/jun/20/time-is-running-out-for-irans-corrupt-mullahs/

Accessed on 24th November 2019