Why corruption still thrives and how can we improve it?

Iraq’s main anti-corruption law is the “Accountability Act” which criminalizes both "active and passive bribery" as well as different forms of corruption such as "extortion, money laundering as well as abuses of power" (Gan Integrity 2018). Despite the presence of anti-corruption measures, the poor enforcement laws in place be derive from a clear lack of compromise between institutional roles as well as the absence of compromise on the part of executive which coupled with unclear governmental legislation and regulatory and poor transparency create an environment conducive of corruptive behaviours (Ibid). In Iraq, money laundering is prosecuted under the “Anti-Money Laundering/Counter-Terrorism Financing Law”, yet the investigatory nature of the government, as well as the limited capacity of the Central Bank, “which works in cooperation with the judiciary and law enforcement authorities to detect and prosecute illicit financial transaction”(Ibid), has been offset by the numerous accounts of informal practices pervading the judiciary and the law enforcement agencies (Ibid). Ironically, Iraq is a member of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC); nevertheless, this is somewhat comical, given that we find cases of public officials who go off the record disclosing the corruptive nature of the executive without facing any form of prosecution. This is further evidenced by the pervasive corruption of the authorities, whose willingness to respect court orders is to a large extent nonexistent. For instance, “Interior Ministry and Justice Ministry employees often extorted bribes from detainees to release them even if the courts had already accorded them the right to be released”(Ibid), yet the lack of accountability of public officials has led to the exception becoming the norm when it comes to the effectiveness of enforcing anti-corruption measures in Iraq.

On a similar note, while Iran’s laws provide for various penalties for corruption, the reality is rather different, in the sense that the law in most cases is rarely applied, and the majority of corruption cases remain unprosecuted ((Gan Integrity 2018). Whilst Iran’s anti-corruption legal framework is clear and concise, it includes certain laws such as the “Act on Public”, the “Revolutionary Courts’ Rules of Procedures in Criminal Matters” as well as the “Aggravating the Punishment for Perpetrators of Bribery, Embezzlement and Fraud Act”, the reality when it comes to prosecution is still equivocal (Ibid). The reason for this can be found in the Iranian judicial system, one of the most relevant branches of government when scrutinising the failure of anti-corruption measures in Iran. As it happens in the case of Iraq, "the judicial system is at high risk of corruption and political interference", evidenced by the numerous instances of cases dismissed by those forming part of the executive branch. This has been evidenced by company executives often bribing and giving irregular payments in exchange for favourable court decisions or in order for cases to be dismissed (Ibid). Iran’s anti-corruption drive has increased over the last few years, yet the inherent system of patronage pervading Iran continues to hamper the effective prosecution of those accused of corruption (Ibid). Moreover, whilst the judiciary is an independent branch from the executive, the head of state (Ali Khamenei) "still possesses absolute power over all different government branches and institutions, including the judiciary" (Ibid). Along these lines, it was evidenced by BTI how “judgments in politically sensitive cases are often determined by intelligence services, and rich and influential individuals are often spared prosecution or farewell in trials” (Ibid), thus corroborating the claim that despite the efforts in anti-corruption campaigns, Iran still lacks effective anti-corruption measures.

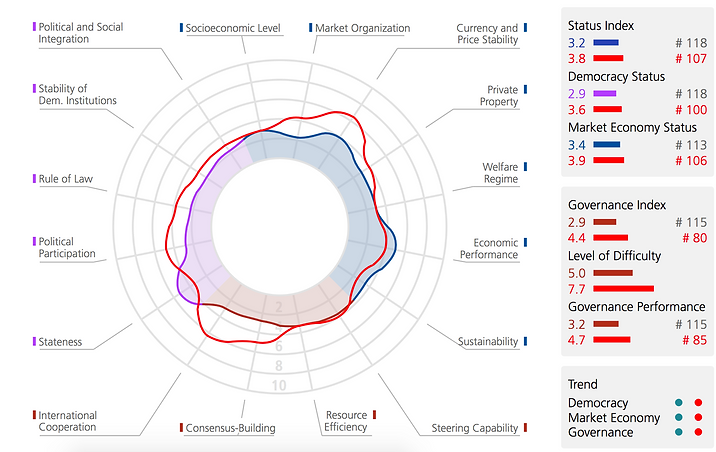

Despite their differences in the Iraq and Iran war that lasted from 1980-1988, the two countries have more in common than just being oil-rich countries in the Middle East. Both studies demonstrate extensive cases of embezzlement, nepotism and bribery under the corruption umbrella. As evidenced by the comparative graph above, most indicators place both nations at the bottom of the socio-politico and economic development line, mostly as a result of the factors we have expounded throughout our country-specific analysis. An Angolan journalist jailed for denouncing the war and corruption fuelled by oil and diamonds in his country once expounded that "It's fashionable to say that we are cursed by our mineral riches. That's not true. We are cursed by our leaders" (Salopek 2000). It would be plausible to debunk such statement by looking at the case of Norway, but this statement rightly captures the essence corruption in nations which are abundant in oil or minerals, as the reality is that the main difference between these two regions is the culture as well as the fact that democracy arrived to Norway before oil was discovered, whereas, in the case of Iran and Iraq, oil was used by already established undemocratic forms of government to pursue their political consolidation as well as their personal enrichment. In light of this great level of informal (and corruptive) governance commonalities found in our analysis, we then propose a few solutions which we argue are paramount in the long term development of both nations:

-

The critical question remains what can be done to free these nations of the current vicious circle of corruption? Thomas Palley argued back in 2003 that a "significant share of oil revenues should be disbursed to the population immediately" (Palley 2003). It would be plausible to reject this suggestion on the grounds of whether the country can afford such a programme. Nevertheless, the oil sector has been for decades the major source of corruption, for this reason, we believe that taking the money out of the hands of the corrupt political elite and transferring it to the population would probably be the most powerful anti-corruption measure available today (Gillies 2010b). Clearly, the anti-corruption schemes shown above have had little to no effect in going after the ‘bad guys'. In light of this, oil disbursements to the population would be an effective measure which would allow the citizenry to regain trust in the executive power, and at the same time, this policy may assuage the rising levels of poverty and may allow families to not rely on many informal practices which are commonplace these days. This solution was supported by both Robert Looney (2008) and Philippe Le Billon (2005), who argued that given the large mineral riches of these two nations, and given the fact that most of the corruption in both nations is the result of oil revenue embezzlement and subsequent conflicts arising from oil management, this solution would be a starting point by tackling the direct source of the problem.

-

A second solution we propose is a new constitution, so that in the case of Iran, citizens may regain trust in the executive by writing a constitution which would include essential elements such as corruption charges and a strong ethics committee which prosecutes the numerous cases of nepotism and embezzlement currently plaguing Iran. In the case of Iraq, we believe this solution would also prove to be a successful venture, as a new constitution would allow Iraqui citizens to benefit from a fresh start, leaving behind all the conflict and sectarianism inherent to the current period, post-2003, and the current political establishment which is dominated, as in the case of Iran, by cases of embezzlement and nepotism. This solution was expounded by Al-Ali (2014), and indeed, a constitution which allows for a reformation of the different government branches would undoubtedly allow for a progressive change and crackdown on former corrupt officials, who would not be protected under a new political framework.

Bibliography

Al-Ali, Z., 2014. The struggle for Iraq's future: how corruption, incompetence and sectarianism have undermined democracy. Yale University Press.

Graph-Atlas BTI 2019, Accessed 9th December 2019, https://atlas.bti-project.org/share.php?1*2018*CV:CTC:SELIRQ*CAT*IRQ*REG: TAB

BTI Country Report on Iraq 2015-2018, Accessed on the 12th December 2019

https://www.bti-project.org/fileadmin/files/BTI/Downloads/Reports/2018/pdf/BTI_2018_Iraq.pdf

BTI Country Report on Iran 2015-2018, Accessed on the 12th December 2019 https://www.bti-project.org/fileadmin/files/BTI/Downloads/Reports/2018/pdf/BTI_2018_Iran.pdf

Le Billon, P., 2005. Corruption, reconstruction and oil governance in Iraq. Third World Quarterly, 26(4-5), pp.685-703.

Looney, R.E., 2008. Reconstruction and peacebuilding under extreme adversity: The problem of pervasive corruption in Iraq. International Peacekeeping, 15(3), pp.424-440.

Palley, T., 2004. Oil and the Case of Iraq. Challenge, 47(3), pp.94-112.

R Marques, cited in P Salopek, ‘CEOs of war bleed Angola’, Chicago Tribune, 2 April 2000.